Poland breaks off from coal and transitions to where?

Poland has been one of the last countries to start to abandon coal and transition towards zero carbon options. No wonder, it was self-sufficient in coal and the trade unions of the industry are also very strong. Until recently, renewable energy had a share of 11% in the energy mix and 14% in the electricity mix.

The country has no nuclear plants. It almost built one in the 1970s-80s but construction was halted in 1982 due to financial problems and then abandoned completely after the Chernobyl disaster. Now, when planning to build one (or rather, some), it also has to build up a workforce capable of operating and maintaining a nuclear power plant and researching nuclear energy.

It is unthinkable for Poland to entrust Russian companies with constructing a nuclear power plant. The two candidates are US and Korean companies, but it is a question whether it is a good idea for a country inexperienced in nuclear energy to experiment with two different nuclear technologies. In addition, France is also interested in building a nuclear power plant but no official plans have been announced yet. Financial uncertainties have already emerged and there are general elections in the autumn of 2023. Meanwhile, based on onshore and offshore wind industry expectations, Poland could be a new hub for wind energy, following in the footsteps of Ireland and Scotland, in addition to opportunities in green hydrogen and energy storage.

We have asked Krzysztof Kobylka, Head of Energy and Climate Programme at WiseEuropa to share his views on the complex situation of his home country.

Which do you think is closer to the truth? Is it that Poland, due to its geographical and economic size (and the size of its energy demand), cannot replace coal in the short time available with anything other than nuclear power - or is it that decarbonisation efforts, at least in Europe, can hardly be imagined based on green energy alone (unless the country has above-average economic potential, such as Germany or Denmark)?

There is really no simple answer to this question, and, in my opinion, the rationale to develop nuclear capacity stems from several factors.

Like you already pointed out, Poland is a relatively large country which, in terms of electricity and heat, is heavily dependent on coal, which accounts for most of the energy mix. Given the necessary pace of decarbonisation, it is true that the Polish government sees nuclear energy as a replacement for some of the soon-to-be decommissioned coal-fired power plants. However, nuclear will not replace all the closing plants and in parallel Poland wants to develop renewable sources. This approach is supposed to enable a more efficient and effective replacement of emission sources, although opponents of nuclear development consider this a waste of finances that could go towards developing projects in renewable energy sources. However, it should be noted that the uptake of RES technologies in Poland is already severely limited compared to investors' appetites due to the allegedly inadequate infrastructure grid, requiring financial and time resources to transform it to a more flexible and dynamic, decentralised grid. Nuclear is supposed to constitute an alternative that does not require the modernisation and expansion of infrastructure in this context and is simpler in this respect.

Another argument, probably the most frequently raised, is energy security and security of supply. Nuclear power is seen as a guarantor of firm power improving the overall security of electricity supply. The Polish government is aiming for a technologically diversified mix, which is in principle more stable and secure. There is certainly also a sentiment in Poland of doubting the viability of basing the energy system on wind and solar. It is also important to remember that Poland is a country with a low share of hydroelectric power plants and an overall low hydrological potential, which further reduces the potential opportunities for dispatchable or firm clean energy development.

We also have the geopolitical and economic factor. Large energy investments with strong partners such as the USA, France, or Korea bind the countries involved economically for years. This has a positive impact on relations with these countries and on strengthening Poland's international position both in terms of security and as a trade/economic partner. The development of nuclear power plants in Poland is also expected to contribute to the growth of new economic branches and to stimulate the country's economy.

In Poland there is also a surprisingly high support for the development of nuclear energy. According to a recent survey commissioned by the Ministry of Climate and Environment, as many as 86% of Poles support the construction of NPPs. This means that the development of nuclear energy is also politically beneficial and is seen as a strength of the state.

If Poland builds nuclear power plants, how do you think this will be reflected in the Polish energy mix over time?

According to the Polish Nuclear Programme, Poland's first nuclear reactor is expected to be operational in 2033. The overall target is 6-9 GW in two power plants with three nuclear units each. The last nuclear unit is to be commissioned in 2043. According to different government declarations, the target is for nuclear power to account for ¼ to 1/3 of electricity production. Thus, in 2040, nuclear would be the third largest source of power generation in Poland after coal and wind. However, one should also bear in mind the plans of companies and ambitious declarations in the field of SMR development, especially those made by Orlen and Synthos. To summarise the declarations made regarding nuclear construction in Poland, there are currently 127 nuclear reactors (sic!) with a total capacity of 36GW (sic!) planned, but it is difficult to say how many of these projects will be executed.

What are the risks and how long are these risks acceptable? The current energy system obviously needs to be fundamentally changed, but there are uncertainties and risks related to the rise of green energy and current developments such as green hydrogen, energy storage, infrastructure development, etc. and there are also potential delays and financial risks involved in nuclear power plant projects. What is the strategy of Poland, how can you go on in this field in a smart way?

The Polish idea for the energy transition is a technologically diversified mix consisting of RES, energy storage, and nuclear power. In the short term, we will also have some gas-fired power plants, mainly for balancing the system and the plan is for coal-fired plants to be phased out entirely in the long term. Poland is certainly a latecomer (late adopter) in Europe when it comes to clean energy transition – it is one of the most carbon-intensive countries and only just catching up on the dynamics of the energy transition. This means that we can look at other countries and learn from their experience. Like other countries, we face several challenges related to RES integration, both technological ones (e.g., related to grid adaptation), as well as those related to legislation, the energy market, heating sector etc., which are being solved as the transition progresses. Let's also remember that as an EU country, we are also affected by the umbrella of EU law, to which we must adapt. From my perspective, EU law has been very helpful to outline a framework for Poland’s transformation, while Poland itself has remained rather sceptical about it for the past two decades.

Also, globally and at the European level, several key technologies (such as PVs, heat pumps, battery storage) are following the learning curve and their cost is consistently declining. Poland should take advantage of these global trends and provide adequate conditions for the development of technologies that contribute to the energy transition in the country. As for nuclear investments, indeed, recent experience, especially in Europe, shows that they involve a high risk of delays and many times higher construction costs. For such projects, it is therefore important to have strong state support and to choose the right partner and proven technology to minimise the risks.

In Poland, one of the main challenges remains the just transition of coal regions. The degree of economic, but also cultural dependence of those regions on coal power, e.g., Upper Silesia, is sometimes underestimated, especially in the West. The Turów power station, for example, which uses coal from a nearby opencast mine, is the sole provider of heat for the town of Bogatynia with a population of 24,000. With a workforce of some 3,500 (power plant and mine), it is the largest employer in the region, with up to 60-70,000 people (including the families of employees and subsidiaries) are dependent on it. This scale of employment is unlikely to be secured by investments in renewable energies unless "gigafactories" are established in such regions. In addition, there is a cultural factor, such as the role of mining for identity, traditions or community life, which back then was often organised by the workplace (sports and cultural facilities, clubs and associations, etc.). The social agreement signed by the Polish government with Silesian miners provides for the phasing out of mines by 2049 according to a set timetable, while at the same time giving miners a guarantee of employment until then, designating a special fund for the transition or investing in research into alternative methods of using coal, to ensure a gradual transition or even make the prospects for the low-carbon use of coal even brighter.

What impact has the war of Russia in Ukraine had on the planning (and implementation) of the Polish energy mix transformation?

Not much has changed for the governmental nuclear programme, it was already quite advanced before the war. More recently, there have been a lot more private initiatives related to SMRs, but it seems to me that they were not so dependent on what happened across the Eastern border, however, there is strong political support for these projects. However, it can be seen as a response to the energy crisis in general, in which the war is a factor - companies saw how unpredictable the energy and commodity markets could be and those who could afford it are planning to secure their own source of electricity and heat. On the declarative side, the war in Ukraine has affected plans for the development of renewable sources. The so far modest energy transition policy has been replaced by a declaration of a much faster development of RES and a faster phasing out of coal, together with the development of new gas capacities with, however, lower utilisation compared to the previous strategy. In my opinion, the increase in ambition was an inevitable and necessary step, the war gave political impetus to change the current direction. However, these are, as I mentioned, solely declarations for now, and time will tell how this will translate into reality.

Currently, Poland has decided on a major US and a major Korean nuclear project, which seems a rather bold move. Since Poland has no nuclear industry background or experience, don't you think it is a huge additional risk to take two different paths at the same time?

In my opinion, the Polish government is playing this quite cleverly. As a country, we want to maintain strong relations both with the Americans, who are our long-standing strategic partner, and with the Koreans, who want to enter the European market, and Poland can be seen as a gateway to this.

From the perspective of energy security, this is, in my opinion, a good move in the long term. Technological diversification, also at the level of other technologies, protects us from, for example, a scenario similar to the French one, in which a failure detected in one reactor stops the entire fleet of the same or a very similar type. In the case of technological diversification, such risks are minimised.

However, as you pointed out, this has its price in the short term. You must develop two parallel (although occasionally intertwined) supply chains, license two different technologies, talk to two contractors, so it means almost twice as much work. This comes with many risks. However, I am convinced that such an investment can pay off in the long term.

Nuclear units other than the Polish ones are also planned in other CEE countries (Czech Republic, Ukraine, Slovenia, Bulgaria) in conditions of very limited resources, e.g., skilled labour, mainly welders. The selection of a single partner could help manage these limited resources, which could be reallocated between different constructions carried out by the same entity. In the case of several projects carried out by competing entities, they will compete for the same limited resources.

It is worth adding that the success of the projects may also be affected by the pending Westinghouse vs. KEPCO/KHNP lawsuit in the federal court for the District of Columbia. The intellectual property case over the APR1400 reactor components is complex and could take several years to resolve. In the meantime, Polish investors in the Korean project must operate in a high degree of uncertainty as to the legal status of Korean technology and the possible blocking of exports by Westinghouse. In the event of a ruling against KHNP and the lack of Westinghouse's goodwill to allow exports to Poland, ZE PAK and PGE will face the choice of abandoning the project or ignoring the US federal court ruling, which, given the nature and importance of PL-US relations, would be highly problematic. Thus, to some extent the WEC vs. KEPCO/KHNP dispute may have a chilling effect on the project. However, it is also worth noting that this dispute could be resolved because of global factors over which Poland has very little influence. Saudi Arabia is also developing its nuclear programme, having excluded Westinghouse from the proceedings for its power plant, with KHNP being one of the admitted bidders. There has been speculation as to whether, given the importance to the US of controlling other countries' civilian nuclear programmes in relation to non-proliferation, South Korea could not become the 'eyes and ears' of the US in SA, potentially resolving the WEC vs KEPCO/KHNP dispute.

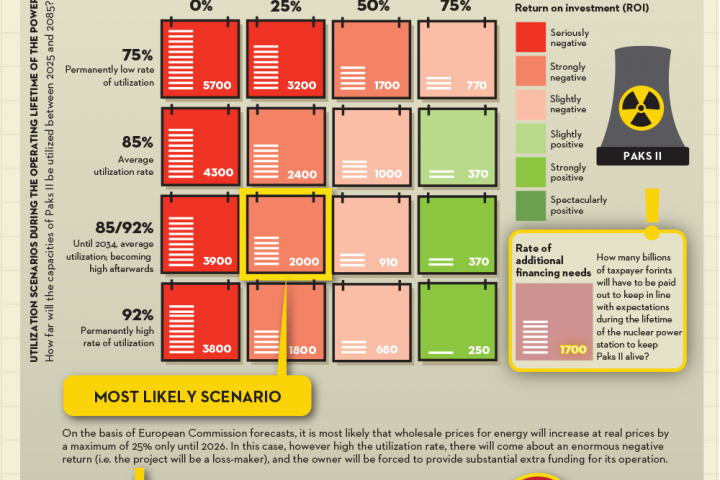

In Hungary, the government's decision in 2014 was to build a new NPP relying on a Russian loan. In ten years they have not even managed to obtain a building permit and this is actually not surprising, as construction in Finland, France and the UK has also been delayed and has become more expensive. What is Poland planning to do to avoid this fiasco?

The financing model for Poland’s nuclear power plant has not yet been confirmed. According to recent information, the AP-1000 consortium (which is at a more advanced stage in its work than the Korean one) has tentatively prepared a model, but it still requires deeper scrutiny to be officially confirmed. Regardless of the model chosen, the strong involvement and support of the Polish state will be pivotal in reducing the risks involved and positively influencing the overall investment. This factor seems to be particularly strong in Poland. As for the constructions in Finland, France, and the UK, let us remember that they were a different type of power plant (the French EPR), as well as the fact that in the case of France and Finland these were the first projects of this type of power plant (the so-called FOAK). At this point, the reactors that are under consideration have already had their first constructions that we, and the constructor, can learn from. Poland has recently focused on selecting a suitable AP1000 contractor to lead the construction. On 25 May 2023, the composition of the consortium was announced: Bechtel will have the role of general contractor, while Westinghouse will be the technology provider and the expert on the technology, not responsible for the construction process itself. Bechtel is an interesting company, with a reputation of being the one to “do others’ dirty work” (also beyond the nuclear sector). When the Vogtle project encountered major challenges and successive contractors (including a giant like Fluor) kept failing, Bechtel was the one to clean it up in the end. Moreover, Bechtel built or was involved in the construction of, majority of nuclear units in the US. Also, I don't think a better contractor could have been chosen for the AP1000 reactor.