First concrete at Paks II – a symbolic milestone, unchanged risks

The pouring of the first concrete at Paks II is a symbolically important moment: from this point on, the project is officially classified as “under construction” according to the criteria of the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA). More precisely, this status applies to Paks-5, the first reactor of the Paks II project. In the case of Paks-6, it is not yet known when construction might begin.

However, this does not mean that we have moved materially closer to Paks II actually generating electricity.

The gap between the official “start” and completion

The start of construction is undoubtedly an important milestone, but in itself it is neither a guarantee of faster progress nor of the project being completed successfully – that is, in line with the original plans. In recent years, several steps that could similarly be described as a “start” have already taken place, from the handover of the site through various preparatory and construction works to the ordering and delivery of certain major components.

So far, these steps have not indicated that the project, which is already delayed by roughly a decade, has meaningfully accelerated, nor that it will certainly reach completion. In other words, construction has now officially begun, but the path towards the plant actually producing electricity remains obstructed by just as many barriers as before.

Known but still active risks

The project continues to be affected by factors that generally complicate nuclear power plant construction:

- financial uncertainties and cost overruns;

- technical and administrative unpreparedness or capacity constraints on the part of the project company and/or the contractor;

- manufacturing and logistical bottlenecks;

- shortages of adequately qualified labour;

- the delaying effects of permitting and inspection processes (partly due to capacity problems within the authorities, partly on the contractor’s side).

Taken together, these factors already carry a significant risk of further delays and cost increases.

Political and legal uncertainty

On top of these issues comes the project’s international political context, shaped by the consequences of the war in Ukraine, which exposes the investment to EU and US sanctions risks.

Further uncertainty was created by the judgment of the Court of Justice of the European Union in September 2025, which annulled the European Commission’s 2017 approval of State aid for the project. The legal and financial consequences of this decision remain unresolved.

Ezekhez adódik hozzá a projekt nemzetközi politikai státusza, amely az ukrajnai háború következményeként alakult ki, és amely miatt a beruházás EU-s és amerikai szankciós kockázatokkal szembesül.

When could Paks II be completed?

Despite a delay of more than a decade, there are still no publicly available, detailed schedules. Public statements consistently remain deliberately vague, for example referring to new units being connected to the grid “in the early 2030s”.

In light of experience, however, this does not appear realistic. The VVER-1200 units planned for Paks have so far been built by Rosatom in Russia and Belarus. Comparable projects have typically taken 9-10 years to complete (while projects in Turkey, Egypt and China are still ongoing). Based on these experiences, completion before 2035 can be ruled out even under optimal conditions.

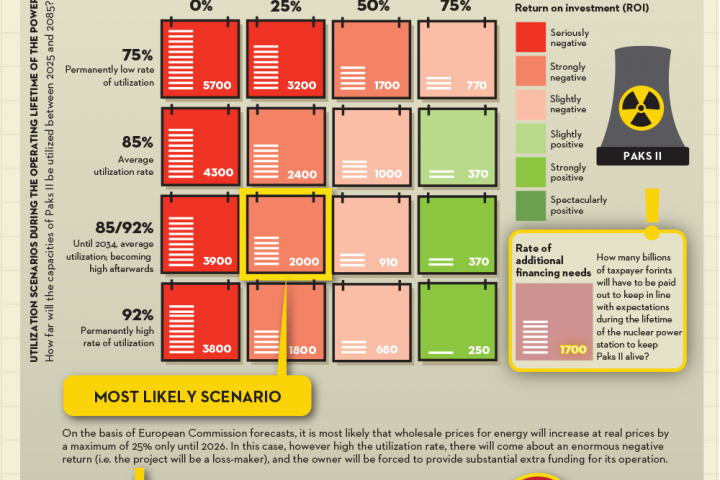

How much will it cost – and who benefits?

It is also unclear how much the investment will ultimately cost. In the meantime, changes in the regulatory framework have made it possible for the project to exceed the originally promised cost of EUR 12.5 billion. Any cost increase directly affects the future market position of the plant: higher costs will inevitably be reflected in the price of electricity.

Market environment: a completely different world from 2014

Even at the launch of the project, it was questionable what kind of market environment Paks II would operate in. Since then, the energy market has undergone a fundamental transformation:

- solar power is spreading at an unprecedented pace;

- energy storage solutions have emerged and are developing rapidly;

- wind power also represents a potential competitor.

Even if the domestic future of wind power remains uncertain, competition does not require all generation capacity to be built in Hungary. Paks II will compete on a regional market, likely with more expensive generation than several of its rivals.

Paks I as an internal competitor

The picture is further complicated by the planned lifetime extension of Paks I. When the contracts for Paks II were signed, the shutdown of Paks I was expected between 2032 and 2035; later, the period of parallel operation was estimated at only a few years. A further extension of up to 20 years, however, would fundamentally alter the market situation.

This could also lead to conflicts over the use of the Danube as cooling water, particularly during summer periods. At present, only very rough ideas exist on how to manage this issue, even though it is crucial from both environmental and economic perspectives.

The issue of missing reserve capacity

There is still no answer as to how Hungary intends to provide the 1,200 MW of reserve capacity required alongside the new 1,200 MW units. Compared to the current level of around 500 MW, this represents a substantial increase, and according to MAVIR, the transmission system operator, the lifetime of existing reserve power plants is also nearing its end.

This means that not 700 MW, but 1,200 MW of new reserve capacity would need to be built.

Conclusion: the questions remain

As we also wrote in last year’s report on nuclear power plant construction, starting construction is only half of the project. Pouring the first concrete does not mark the end of difficulties; on the contrary, it is likely to signal the beginning of new obstacles that cause further delays and cost overruns. Experience shows that the completion date is often uncertain and frequently “disappears into the mists of time”.

Overall, there remain numerous unanswered questions regarding the economic and energy rationale of Paks II, which is already delayed by roughly a decade. All this suggests that the project is driven primarily by unclear political intentions rather than by clear economic and energy-related arguments.