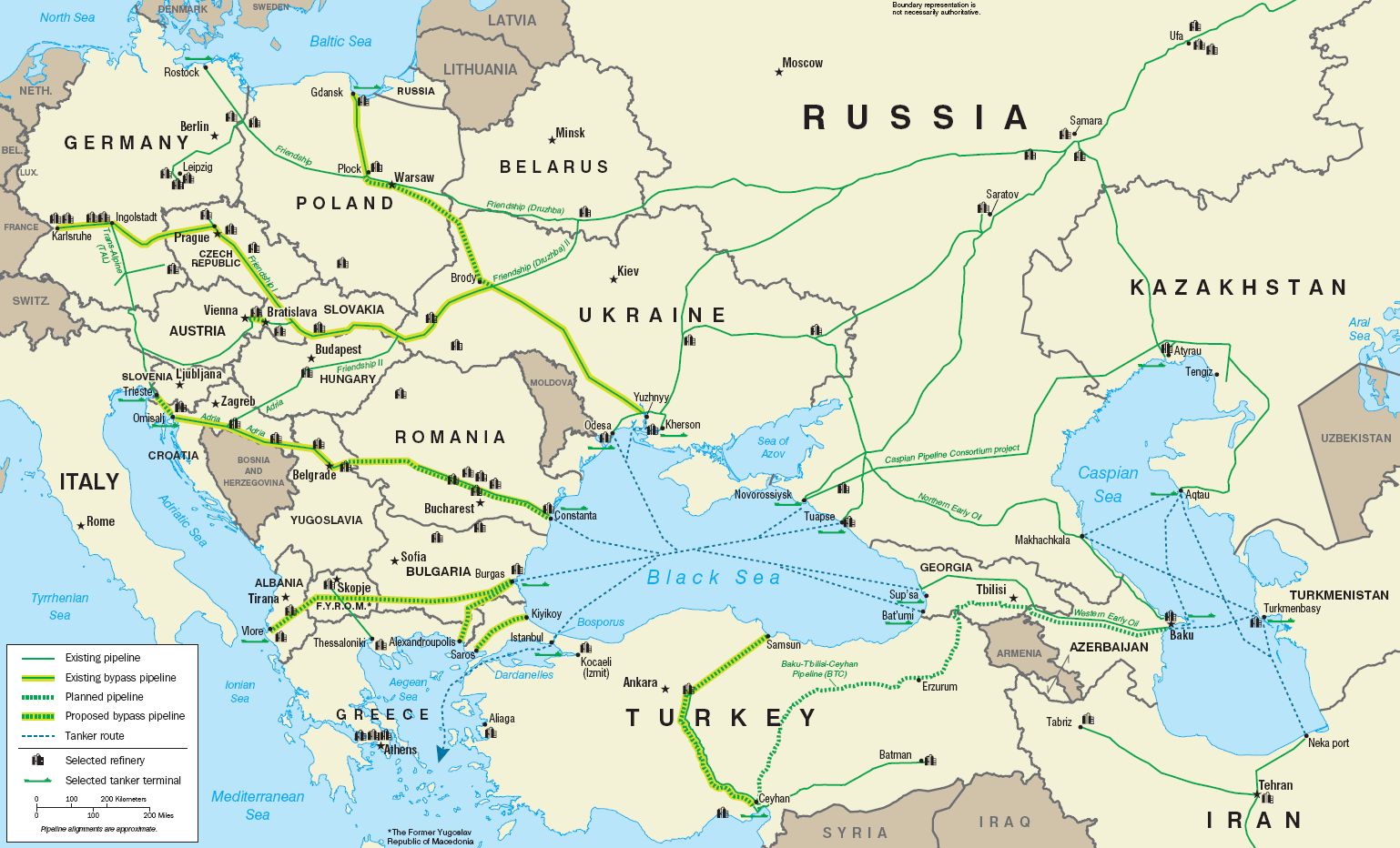

The Druzhba Pipeline (Friendship Pipeline) and the Legend of a Self-Reliant Energy Policy

Government communication has recently sought to revive a quaintly old-fashioned expression: in the name of striving for sovereignty, the government dreams of a “self-reliant energy policy.” The word "magabíró" (in english: "self-reliant") itself means “healthy, able to endure work, hardship, and struggle well,” or, in a slightly more archaic sense, “someone with enough strength not to depend on others or on help.” We are not sure whether the expression can be applied to abstract concepts, but we will leave that to linguists and instead examine to what extent it may stand when it comes to energy policy, in light of the recent attacks on the Friendship pipeline.

As for “self-reliance,” government communication ties it on the one hand to renewables and on the other hand to increasing domestic oil and gas production. We agree with the self-reliance of renewables: the boom of recent years has propelled solar power to second place in terms of domestically generated electricity (on an annual basis, and this summer solar power plants were already competing for first place with Paks, which was mostly operating with three blocks due to maintenance). This has significantly reduced not only imported electricity but also the amount of imported natural gas used, thanks to the decline of gas-fired power plants. What is more, from spring to autumn, there is typically even ample electricity available for export during the day. Of course, solar power would need to be complemented by wind, geothermal, and other locally available renewables (e.g., biogas), as well as the development of energy storage. The government woke up late to these opportunities; the pace could be faster, and so far the ongoing programs have had no tangible effect.

With oil, however, the situation is visibly quite different. Despite domestic production increasing by 10–15% in recent years, this barely reduced the roughly 90% import share. In other words, we remain heavily dependent on oil imports, and that can hardly be called “self-reliant.”

This is the point where communication sharply diverges: on the one hand, speaking of sovereignty and “self-reliance,” and on the other, complaining about the attacks on the oil pipeline while playing up the victim role. The fact is that the roughly 85–90% import share of oil and gas represents serious exposure even in peacetime. With the outbreak of the war in Ukraine, the supply risk – at least in the case of oil, via the Friendship pipeline running through Ukraine – has, quite obviously, increased significantly.

We can attach all sorts of labels to energy policy, but its resilience in times of crisis will not be decided by Facebook posts and press statements. Even without in-depth military strategic knowledge, it was easy to see as early as 2022 that Hungary could not behave as if a war had not broken out next door. It would have been in Hungary’s own well-understood interest to start making provisions for a Plan B. It cannot be emphasised enough: the responsibility for guaranteeing the security of energy supply lies with the government of the day.

The war has been going on for three and a half years now, and the events of recent weeks suggest that the situation has reached the point where military operations are already threatening the Russian oil industry itself, including the Friendship oil pipeline. A likely scenario is that this situation will become permanent, meaning that in the coming months forced shutdowns of the pipeline may occur with some regularity, and in fact supplies may be interrupted for longer periods.

In the coming months, it will most likely become clear whether the government and MOL have prepared for such a scenario or whether they were content with dependence on a single pipeline, somehow trusting that “nothing would go wrong.”

It is not particularly reassuring that so far the Hungarian government has revealed little about what has been done to reduce our exposure to an oil pipeline running through a war zone. It also raises questions about whether, according to MOL, the conversion of the Százhalombatta refinery to process types of crude other than Russian oil would still cost around HUF 200 billion (~USD 500–600 million) and still take about two years, as they stated in 2023 (while experts argued that it could have been solved with a few tens of millions of dollars). With immediate action, we could already have reached the point of enabling such a conversion for an amount that is acceptable compared to both MOL Group’s budget and the war-related risks—even if it were USD 500 million, considering that MOL Group’s 2023 pre-tax profit was USD 1.936 billion. It is possible that progress has been made, but in the absence of information, the extent of it is questionable.

Of course, the best solution would be to take measures that reduce the fossil dependence that still dominates our energy supply. Beyond the exposure and the war in Ukraine, this is also justified by the environmental destruction and climate-damaging effects of fossil fuels. Regardless of the rapid development of renewable energy sources, the phasing out of fossil fuels should in any case proceed at a much faster pace.

📷 Fortepan / Urbán Tamás